- Home

- Graham Hancock

Fingerprints of the Gods Page 30

Fingerprints of the Gods Read online

Page 30

was the hissing of steam. All living things, all plant life, were blotted out. Only the

naked soil remained, but like the sky itself the earth was no more than cracks and

crevasses.

And now all the rivers, all the seas, rose and overflowed. From every side waves

lashed against waves. They swelled and boiled slowly over all things. The earth

sank beneath the sea ...

Yet not all men perished in the great catastrophe. Enclosed in the wood itself of

the ash tree Yggdrasil—which the devouring flames of the universal conflagration

had been unable to consume—the ancestors of a future race of men had escaped

death. In this asylum they had found that their only nourishment had been the

morning dew.

Thus it was that from the wreckage of the ancient world a new world was born.

Slowly the earth emerged from the waves. Mountains rose again and from them

streamed cataracts of singing waters.27

The new world this Teutonic myth announces is our own. Needless to say,

like the Fifth Sun of the Aztecs and the Maya, it was created long ago and

is new no longer. Can it be a coincidence that one of the many Central

American flood myths about the fourth epoch, 4 Atl (‘water’), does not

install the Noah couple in an ark but places them instead in a great tree

just like Yggdrasil? ‘ 4 Atl was ended by floods. The mountains

disappeared ... Two persons survived because they were ordered by one

of the gods to bore a hole in the trunk of a very large tree and to crawl

inside when the skies fell. The pair entered and survived. Their offspring

repopulated the world.’28

Isn’t it odd that the same symbolic language keeps cropping up in

ancient traditions from so many widely scattered regions of the world?

How can this be explained? Are we talking about some vast, subconscious

wave of intercultural telepathy, or could elements of these remarkable

universal myths have been engineered, long ages ago, by clever and

purposeful people? Which of these improbable propositions is the more

likely to be true? Or are there other possible explanations for the enigma

of the myths?

We shall return to these questions in due course. Meanwhile, what are

we to conclude about the apocalyptic visions of fire and ice, floods,

volcanism and earthquakes, which the myths contain? They have about

them a haunting and familiar realism. Could this be because they speak

to us of a past we suspect to be our own but can neither remember

clearly nor forget completely?

27 New Larousse Encyclopaedia of Mythology, pp. 275-7.

28 Maya History and Religion, p. 332.

202

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

Chapter 26

A Species Born in the Earth’s Long Winter

In all that we call ‘history’—everything we clearly remember about

ourselves as a species—humanity has not once come close to total

annihilation. In various regions at various times there have been terrible

natural disasters. But there has not been a single occasion in the past

5000 years when mankind as a whole can be said to have faced

extinction.

Has this always been so? Or is it possible, if we go back far enough,

that we might discover an epoch when our ancestors were nearly wiped

out? It is just such an epoch that seems to be the focus of the great

myths of cataclysm. Scholars normally attribute these myths to the

fantasies of ancient poets. But what if the scholars are wrong? What if

some terrible series of natural catastrophes did reduce our prehistoric

ancestors to a handful of individuals scattered here and there across the

face of the earth, far apart, and out of touch with one another?

We are looking for an epoch that will fit the myths as snugly as the

slipper on Cinderella’s foot. In this search, however, there is obviously no

point in investigating any period prior to the emergence on the planet of

recognizably modern human beings. We’re not interested here in Homo

habilis or Homo erectus or even Homo sapiens neanderthalensis. We’re

interested only in Homo sapiens sapiens, our own species, and we haven’t

been around very long.

Students of early Man disagree to some extent over how long we have

been around. Some researchers, as we shall see, claim that partial human

remains in excess of 100,000 years old may be ‘fully modern’. Others

argue for a reduced antiquity in the range of 35-40,000 years, and yet

others propose a compromise of 50,000 years. But no one knows for

sure. ‘The origin of fully modern humans denoted by the subspecies

name Homo sapiens sapiens remains one of the great puzzles of

palaeoanthropology,’ admits one authority.1

About three and a half million years of more or less relevant evolution

are indicated in the fossil record. For all practical purposes, that record

starts with a small, bipedal hominid (nicknamed Lucy) whose remains

were discovered in 1974 in the Ethiopian section of East Africa’s Great

Rift Valley. With a brain capacity of 400cc (less than a third of the modern

average) Lucy definitely wasn’t human. But she wasn’t an ape either and

she had some remarkably ‘human-like’ features, notably her upright gait,

and the shape of her pelvis and back teeth. For these and other reasons,

1 Roger Lewin, Human Evolution, Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, 1984, p. 74.

203

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

her species—classified as Australopithecus afarensis— has been accepted

by the majority of palaeoanthropologists as our earliest direct ancestor.2

About two million years ago representatives of Homo habilis, the

founder members of the Homo line to which we ourselves belong, began

to leave their fossilized skulls and skeletons behind. As time went by this

species showed clear signs of evolution towards an ever more ‘gracile’

and refined form, and towards a larger and more versatile brain. Homo

erectus, who overlapped with and then succeeded Homo habilis,

appeared about 1.6 million years ago with a brain capacity in the region

of 900cc (as against 700cc in the case of habilis).3 The million or so years

after that, down to about 400,000 years ago, saw no significant

evolutionary changes—or none attested to by surviving fossils. Then

Homo erectus passed through the gates of extinction into hominid

heaven and slowly—very, very slowly—what the palaeoanthropologists

call ‘the sapient grade’ began to appear:

Exactly when the transition to a more sapient form began is difficult to establish.

Some believe the transition, which involved an increase in brain size and a

decrease in the robustness of the skull bones, began as early as 400,000 years

ago. Unfortunately, there are simply not enough fossils from this important period

to be sure about what was happening.’4

What was definitely not happening 400,000 years ago was the emergence

of anything identifiable as our own story-telling, myth-making subspecies

Homo sapiens sapiens. The consensus is that ‘sapient humans must have

evolved from Homo erectus’,5 and it is

true that a number of ‘archaic

sapient’ populations did come into existence between 400,000 and

100,000 years ago. Unfortunately, the relationship of these transitional

species to ourselves is far from clear. As noted, the first contenders for

membership of the exclusive club of Homo sapiens sapiens have been

dated by some researchers to the latter part of this period. But these

remains are all partial and their identification is by no means universally

accepted. The oldest, part of a skullcap, is a putative modern human

specimen from about 113,000 BC.6 Around this date, too, Homo sapiens

neanderthalensis first appears, a quite distinct subspecies which most of

us know as ‘Neanderthal Man’.

Tall, heavily muscled, with prominent brow ridges and a protruding

face, Neanderthal Man had a bigger average brain size than modern

humans (1400cc as against our 1360cc).7 The possession of such a big

brain was no doubt an asset to these ‘intelligent, spiritually sensitive,

2 Donald C. Johanson and Maitland C. Eddy, Lucy: The Beginnings of Humankind,

Paladin, London, 1982, in particular, pp. 28, 259-310.

3 Roger Lewin, Human Evolution, pp. 47-49, 53-6; Encyclopaedia Britannica, 6:27-8.

4 Human Evolution, p. 76.

5 Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1991, 18:831.

6 Human Evolution, p. 76.

7 Ibid., p. 72.

204

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

resourceful creatures’8 and the fossil record suggests that they were the

dominant species on the planet from about 100,000 years ago until

40,000 years ago. At some point during this lengthy and poorly

understood period, Homo sapiens sapiens established itself, leaving

behind fossil remains from about 40,000 years ago that are undisputably

those of modern humans, and supplanting the Neanderthals completely

by about 35,000 years ago.9

In summary, human beings like ourselves, whom we could pass in the

street without blinking an eyelid if they were shaved and dressed in

modern clothes, are creatures of the last 115,000 years at the very

most—and more probably of only the last 50,000 years. It follows that if

the myths of cataclysm we have reviewed do reflect an epoch of

geological upheaval experienced by humanity, these upheavals took place

within the last 115,000 years, and more probably within the last 50,000

years.

Cinderella’s slipper

It is a curious coincidence of geology and palaeoanthropology that the

onset and progress of the last Ice Age, and the emergence and

proliferation of modern Man, more or less shadow each other. Curious

too is the fact that so little is known about either.

In North America the last Ice Age is called the Wisconsin Glaciation

(named for rock deposits studied in the state of Wisconsin) and its early

phase has been dated by geologists to 115,000 years ago.10 There were

various advances and retreats of the ice-cap after that, with the fastest

rate of accumulation taking place between 60,000 years ago and 17,000

years ago—a process culminating in the Tazewell Advance, which saw the

glaciation reach its maximum extent around 15,000 BC.11 By 13,000 BC,

however, millions of square miles of ice had melted, for reasons that have

never properly been explained, and by 8000 BC the Wisconsin had

withdrawn completely.12

The Ice Age was a global phenomenon, affecting both the northern and

the southern hemispheres; similar climatic and geological conditions

therefore prevailed in many other parts of the world as well (notably in

eastern Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and South America). There was

massive glaciation in Europe, where the ice reached outward from

Scandinavia and Scotland to cover most of Great Britain, Denmark,

Poland, Russia, large parts of Germany, all of Switzerland, and big chunks

8 Ibid., p. 73.

9 Ibid., p. 73, 77.

10 Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1991, 12:712.

11 Path of the Pole, p. 146.

12 Ibid., p. 152; Encyclopaedia Britannica, 12:712.

205

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

of Austria, Italy and France.13 (Known technically as the Wurm Glaciation,

this European Ice Age started about 70,000 years ago, a little later than

its American counterpart, but attained its maximum extent at the same

time, 17,000 years ago, and then experienced the same rapid withdrawal,

and shared the same terminal date).14

The crucial stages of Ice Age chronology thus appear to be:

1 around 60,000 years ago, when the Wurm, the Wisconsin and other

glaciations were well under way;

2 around 17,000 years ago, when the ice sheets had reached their

maximum extent in both the Old World and the New;

3 the 7000 years of deglaciation that followed.

The emergence of Homo sapiens sapiens thus coincided with a lengthy

period of geological and climatic turbulence, a period marked, above all

else, by ferocious freezing and flooding. The many millennia during

which the ice was remorselessly expanding must have been terrifying and

awful for our ancestors. But those final 7000 years of deglaciation,

particularly the episodes of very rapid and extensive melting, must have

been worse.

Let us not jump to conclusions about the state of social, or religious, or

scientific, or intellectual development of the human beings who lived

through the sustained collapse of that tumultuous epoch. The popular

stereotype may be wrong in assuming that they were all primitive cave

dwellers. In reality little is known about them and almost the only thing

that can be said is that they were men and women exactly like ourselves

physiologically and psychologically.

It is possible that they came close to total extinction on several

occasions during the upheavals they experienced; it is also possible that

the great myths of cataclysm, to which scholars attribute no historical

value, may contain accurate records and eyewitness accounts of real

events. As we see in the next chapter, if we are looking for an epoch that

fits those myths as snugly as the slipper on Cinderella’s foot, it would

seem that the last Ice Age is it.

13 John Imbrie and Katherine Palmer Imbrie, Ice Ages: Solving the Mystery, Enslow

Publishers, New Jersey, 1979, p. 11.

14 Ibid., p. 120; Encyclopaedia Britannica, 12:783; Human Evolution, p. 73.

206

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

Chapter 27

The Face of the Earth was Darkened

and a Black Rain Began to Fall

Terrible forces were unleashed on all living creatures during the last Ice

Age. We may deduce how these afflicted humanity from the firm evidence

of their consequences for other large species. Often this evidence looks

puzzling. As Charles Darwin observed after visiting South America:

No one I think can have marvelled more at the extinction of species than I have

done. When I found in La Plata [Argentina] the tooth of a horse embedded with the

remains of Mastodon, Megatherium, Toxodon, and other extinct monsters, which

all co-existed at a ve

ry late geological period, I was filled with astonishment; for

seeing that the horse, since its introduction by the Spaniards in South America,

has run wild over the whole country and has increased its numbers at an

unparalleled rate, I asked myself what could have so recently exterminated the

former horse under conditions of life apparently so favourable?1

The answer, of course, was the Ice Age. That was what exterminated the

former horses of the Americas, and a number of other previously

successful mammals. Nor were extinctions limited to the New World. On

the contrary, in different parts of the earth (for different reasons and at

different times) the long epoch of glaciation witnessed several quite

distinct episodes of extinction. In all areas, the vast majority of the many

destroyed species were lost in the final seven thousand years from about

15,000 BC down to 8000 BC.2

At this stage of our investigation is it not necessary to establish the

specific nature of the climatic, seismic and geological events linked to the

various advances and retreats of the ice sheets which killed off the

animals. We might reasonably guess that tidal waves, earthquakes,

gigantic windstorms and the sudden onset and remission of glacial

conditions played their parts. But more important—whatever the actual

agencies involved—is the stark empirical reality that mass extinctions of

animals did take place as a result of the turmoil of the last Ice Age.

This turmoil, as Darwin concluded in his Journal, must have shaken ‘the

entire framework of the globe’.3 In the New World, for example, more

than seventy genera of large mammals became extinct between 15,000

BC and 8000 BC, including all North American members of seven families,

and one complete order, the Proboscidea.4 These staggering losses,

1 Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species, Penguin, London, 1985, p. 322.

2 Quaternary Extinctions, pp. 360-1, 394.

3 Charles Darwin, Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of

Countries Visited during the Voyage of HMS Beagle Round the World; entry for 9 January

1834.

4 Quaternary Extinctions, pp. 360-1, 394.

207

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

involving the violent obliteration of more than forty million animals, were

not spread out evenly over the whole period; on the contrary, the vast

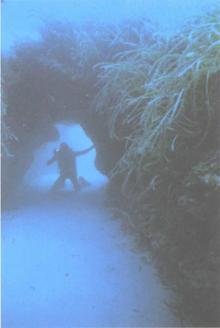

Underworld: The Mysterious Origins of Civilization

Underworld: The Mysterious Origins of Civilization The Master Game: Unmasking the Secret Rulers of the World

The Master Game: Unmasking the Secret Rulers of the World America Before

America Before Entangled

Entangled War God: Nights of the Witch

War God: Nights of the Witch War God: Return of the Plumed Serpent

War God: Return of the Plumed Serpent The Message of the Sphinx AKA Keeper of Genesis

The Message of the Sphinx AKA Keeper of Genesis Fingerprints of the Gods

Fingerprints of the Gods The Sign and the Seal

The Sign and the Seal The Mars Mystery: The Secret Connection Between Earth and the Red Planet

The Mars Mystery: The Secret Connection Between Earth and the Red Planet Magicians of the Gods: The Forgotten Wisdom of Earth's Lost Civilization

Magicians of the Gods: The Forgotten Wisdom of Earth's Lost Civilization War God

War God Underworld

Underworld The Mars Mystery

The Mars Mystery Magicians of the Gods

Magicians of the Gods The Master Game

The Master Game