- Home

- Graham Hancock

Magicians of the Gods: The Forgotten Wisdom of Earth's Lost Civilization Page 3

Magicians of the Gods: The Forgotten Wisdom of Earth's Lost Civilization Read online

Page 3

“Made to be buried?” I’m intrigued. I’m waiting for him to say “as a time capsule” but instead he replies, “Like, for example, the megalithic cemeteries in Western Europe—huge constructions and then a mound on top.”

“But then they’re for burial of bodies. Is there any evidence of burial of bodies here?”

“We don’t have burials yet. We have some fragments of human bones mixed in with animal bones within the filling material but no burials at the moment. We expect we will find some soon.”

“So you believe Göbekli Tepe was a necropolis?”

“It still has to be proved. But that’s my hypothesis, yes.”

“And those fragments of human bones you’ve found mixed with animal bones in infill. What do you make of those? Sacrifice? Cannibalism?”

“I don’t think so. My guess is that those bones are evidence of some special treatment of the human body after death—perhaps deliberate excarnation. Such rites were practiced at a number of other known sites in this region that are of about the same age. For me the presence of human bones in the filling material strengthens the hypothesis that we will find primary burials somewhere at Göbekli Tepe, burials that were opened after some time for a continuation of very specific rituals performed with the dead.”12

“What, then, was the function of the pillars?”

“The T-shaped pillars are certainly anthropomorphic, yet often with animals depicted on them, perhaps telling us stories connected with the T-shaped beings. We cannot be sure, of course, but I think they represent divine beings.”

“And even when they’re not T-shaped?” I point to the lion pillar. “Like this one? It too has an animal depicted upon it.”

Schmidt shrugs. “We cannot know for sure. Perhaps we will never know. There is so much mystery here. We could excavate for fifty years and still not find all the answers. We are just at the beginning.”

“But even so you do have some answers. You clearly have some ideas. This lion pillar, for example. Are you at least able to say how old it is?”

“Honestly we don’t know. When we excavate beneath it we will hopefully find some organic material that we can carbon date. But until we do we can’t be sure.”

“But what’s your impression from the style?”

Schmidt shrugs again before conceding, a little begrudgingly, “It looks similar to some of the pillars in Enclosure C.”

“Which are the oldest?”

“Yes—so something of that age.”

“And that would be what exactly?”

“Exactly 9600 BC, calibrated, is the earliest date we have.”

Radiocarbon years and calendar years drift further and further apart as time goes by because the amount of the radioactive isotope carbon-14 in the atmosphere and in all living, organic, things varies from epoch to epoch. Fortunately scientists have found ways—too complicated to go into at this point—to correct for such fluctuations. The process is called calibration so when Schmidt says “9600 BC calibrated” he is giving me calendar years. What “9600 BC calibrated” means in 2013 when I’m talking to him is therefore 9600 years plus the 2013 years that have elapsed since the time of Christ—i.e. 11,613 years ago. I am writing this sentence in December 2014 and you might not read it until 2016, by which time that oldest date that Schmidt is referring to will work out at 11,616 years before the present.

You get the idea.

In other words, put simply, and in round numbers, the oldest parts of Göbekli Tepe to have been excavated so far are a little over 11,600 years old. And, despite all the cautions and qualifications he has expressed, what Schmidt is telling me is that in his informed opinion, on stylistic grounds, the lion-pillar we are looking at is likely to be at least as old as anything hitherto excavated at Göbekli Tepe.

Indeed, although he hasn’t said so much—there’s very little evidence one way or the other—the possibility has to be considered that it might even be older. After all, he’s already admitted that the best work at Göbekli Tepe is the oldest. It’s troubling, therefore, despite the hope he’s expressed that further excavation will reveal “the small beginnings that we expect but haven’t yet found,” that this first piece of further excavation has in fact uncovered no such “small beginnings.” On the contrary what it has brought to light is a massive, superbly executed megalithic pillar, with a lion rampant carved upon it in exquisite high relief, that appears, at least on stylistic grounds, to be extremely old.

Perhaps, rather than Schmidt’s hoped-for “small beginnings,” further excavations will only uncover more of the same?

“We know the end,” the Professor tells me firmly. “The youngest layers at Göbekli Tepe date to 8200 BC. That’s when the site is abandoned forever. But we don’t know the beginning yet.”

“Except that date of 9600 BC, 11,600 years ago, that you have from Enclosure C. That’s the beginning—at least as far as you’ve been able to establish it up to now?”

“The beginning of the monumental phase, yes.” There’s a glint in the Professor’s eye. “And you know, 9600 BC is an important date. It isn’t just a number. It’s the end of the Ice Age. It’s a global phenomenon. So since this goes in parallel—”

The date Schmidt is putting such emphasis on rings a sudden bell in my mind, relating to other research I’ve been doing, and I feel compelled to interrupt.

“9600 BC! That’s not just the end of the Ice Age. It’s the end of the Younger Dryas cold spell that starts in, what—10,800 BC?”

“And ends in 9620 BC,” Schmidt continues, “according to the ice cores from Greenland. So how likely is it to be an accident that the monumental phase at Göbekli Tepe starts in 9600 BC when the climate of the whole world has taken a sudden turn for the better and there’s an explosion in nature and in possibilities?”

I can only agree. It doesn’t seem likely that it’s an accident at all. On the contrary, I feel certain there must be a connection. We’ll explore that connection, and the mysterious cataclysmic period that geologists call the Younger Dryas—and what those Greenland ice cores tell us—in Part II.

Meanwhile, back in 2013, I close my interview with Klaus Schmidt with some praise. And in December 2014, as I sit at my desk going through the transcript of the recording I made at Göbekli Tepe, and knowing that Klaus died of a massive, unexpected heart attack on July 20, 2014, I’m glad I did so. “You’re a very humble man,” I say. “But the fact is you’ve discovered a site that has caused us all to rethink our ideas of the past. This is a remarkable thing and I believe that your name, as well as the name of Göbekli Tepe, will go down in history.”

The bringers of civilization

After leaving Göbekli Tepe in mid-September 2013, I make an extensive journey throughout the length and breadth of Turkey before I finally return home.

The lion pillar sticks in my mind, but what particularly haunts me is the scene on Pillar No. 43 in Enclosure D—the scene showing the vulture with its bent human-like knees, and its wing that so much resembles an arm, holding up a solid disc.

I download Santha’s photographs onto my computer and call up that scene. It has many remarkable elements as well as the disc. Both wings of the vulture are shown, I now realize, the other stretched out behind its body. To the right of the vulture is a serpent. It has a large triangular head, as do all serpents depicted at Göbekli Tepe, and its body is coiled into a curve with its tail extending down toward an “H”-shaped pictogram. The serpent is nestled close to another large bird—not a vulture but something more like an Ibis with a long, sickle-shaped beak. Between it and the vulture is yet another bird, again with a hooked beak, but smaller, with the look of a chick.

I turn my attention to the disc. I don’t know what to make of it, but the obvious guess from its shape is that it’s meant to represent the sun.

There’s something else that interests me more, however, if I can just put my finger on what it is—something evocative, something hauntingly familiar, about the imagery on thi

s ancient pillar from Göbekli Tepe. Santha has shot hundreds of frames of it, from every possible angle, and obsessively I keep going through them, hoping for some clue. The vulture … the disc … and in the next register above the vulture, that weird row of bags, with their curved handles …

Bags.

Handbags.

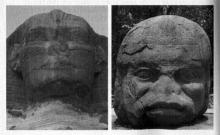

Suddenly I get it. I go to the shelf in my library where I keep reference copies of my own books, pull out Fingerprints of the Gods, and start leafing through the photo sections. The first section deals with South America and what I’m looking for isn’t there. But the second section is devoted to Mexico and, on the fifth page, I find it. It’s image number 33 with the caption: “Man in Serpent sculpture from the Olmec site of La Venta.” It’s Santha’s photograph, taken way back in 1992 or 1993, of an impressive relief carved on a slab of solid granite measuring about 1.2 meters (4 feet) wide and 1.5 meters (5 feet) high. The relief features what is believed to be the earliest representation of the Central American deity whom the Maya (a later civilization than the Olmecs) would call Kukulkan or Gucumatz, and who was known by the even later Aztecs as Quetzalcoatl.13 All three names mean “Feathered Serpent” (sometimes translated as “Plumed Serpent”) and it is such a serpent, decorated with a prominent feathered crest on its head, that we see here. Its powerful body coils sinuously around the outer edge of the relief, cradling the figure of a man who is depicted in a seated position as though he is reaching for pedals with his feet. In his right hand he is holding what I described at the time as “a small, bucket-shaped object.”14

Figure 5: “Man in Serpent” sculpture—the earliest surviving representation of the Central American deity later known as Quetzalcoatl.

I return to Santha’s images from Enclosure D at Göbekli Tepe and am immediately able to confirm what I suspected. The three bags on the pillar closely resemble the “bucket-shaped” object from La Venta in Mexico. The same curved handle is there in both cases and the profile of the “bags” and of the “bucket”—slightly wider at the bottom than at the top—is also very similar.

If that were all there was to it, this would surely be a coincidence. The “Man in Serpent” relief from La Venta is thought by archaeologists to date to the period between the tenth and the sixth centuries BC15—about nine thousand years younger than the imagery from Göbekli Tepe—so how could there possibly be a connection?

That’s when I remember a second curious image I reproduced in Fingerprints of the Gods. I check the index for the name Oannes, turn to Chapter Eleven, and find another figure of a man carrying a bag or bucket. I hadn’t noticed the resemblance between it and “Man in Serpent” before but it’s obvious to me now. Although not absolutely identical, both bags have the same curved handle that is also depicted on the Göbekli Tepe pillar. Quickly I scan through the report I wrote twenty years earlier. Oannes was a civilizing hero revered by all the ancient cultures of Mesopotamia. He was said to have appeared there in the remotest antiquity and to have taught the inhabitants:

the skills necessary for writing and for doing mathematics and for all sorts of knowledge: how to build cities, found temples … make laws … determine borders and divide land, also how to plant seeds and then to harvest their fruits and vegetables. In short [he] taught men all those things conducive to a civilized life.16

The fullest account we have of Oannes is found in surviving fragments of the works of a Babylonian priest called Berossos who wrote in the third century BC. Fortunately I have a translation of all the Berossos fragments in one volume in my library so I dig it out along with a few other sources on ancient Mesopotamian myths and traditions. It doesn’t take me long to discover that Oannes did not do his work alone but was supposedly the leader of a group of beings known as the Seven Apkallu—the “Seven Sages”—who were said to have lived “before the flood” (a cataclysmic global deluge features prominently in many Mesopotamian traditions, including those of Sumer, Akkad, Assyria and Babylon). Alongside Oannes, these sages are portrayed as bringers of civilization who, in the most ancient past, gave humanity a moral code, arts, crafts and agriculture and taught them architectural, building and engineering skills.17

Figure 6: Oannes, a civilizing hero from before the flood, revered by all the ancient cultures of Mesopotamia. The reasons for his strange clothing or costume—he is often referred to as a “fish-garbed figure”—are given in Chapter 8.

That’s a list, I can’t help thinking, that includes all the skills supposedly “invented” at Göbekli Tepe!

I call up a map on my computer screen and see that not only does southeastern Turkey adjoin Mesopotamia geographically but also that the two areas are linked in an even more intimate and direct way. Largely occupied today by the modern state of Iraq, the ancient name Mesopotamia means, literally, “[land] between rivers”—the rivers in question being the Tigris and the Euphrates, which reach the sea in the Persian Gulf, but which both have their headwaters in the same Taurus mountain range of southeastern Turkey where Göbekli Tepe is situated.

Figure 7: Location of Gobekli Tepe in relation to the headwaters of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers of Mesopotamia

While I’m online I run some searches for images of the Seven Sages. I don’t get many hits at first, but the moment I change the search terms to “Apkallu” and “Seven Apkallu” I open a colossal archive of images from all over the internet, many of them reliefs from Assyria, a culture that thrived in Mesopotamia from approximately 2500 BC to about 600 BC. I add “Assyrian Apkallu” to the search parameters and even more images flood my screen. Often they show bearded men holding bags or buckets which closely resemble those depicted on the Göbekli Tepe pillar and the one held by the Mexican “Man in Serpent” figure. It’s not just the curved handles of these containers, or their shape—where the resemblance is much closer than on the original Oannes relief I reproduced in Fingerprints of the Gods. Even more striking is the peculiar and distinctive way that the figures from both Mesopotamia and Mexico hold these containers with the fingers of the hands turned inward and the thumb crooked forward over the handle.

There’s something else as well. A good number of the images show not a man but a therianthrope—a birdman with a hooked beak exactly like the hooked beak of the therianthrope on the Göbekli Tepe pillar. What makes the resemblance even closer is that in the Mesopotamian reliefs the birdman is holding the container in one hand and a cone-shaped object in the other. The shape is a little different but a comparison with the disc cradled above the wing of the Göbekli Tepe birdman is hard to resist.

I can’t prove anything yet. It could, of course, all be coincidence, or I could be imagining links that aren’t there. But my curiosity is aroused by the similar containers on different continents and in different epochs and so I jot down a series of questions that can form the frame of a loose hypothesis for future testing. For instance, could these containers (whether they are bags or buckets) be the symbols of office of an initiatic brotherhood—far traveled and deeply ancient, with roots reaching back into the remotest prehistory? I feel that this possibility, extraordinary though it may seem on the face of things, is worth looking into and is strengthened by the distinctive hand postures. Might these not have served the same sort of function as Masonic handshakes today—providing an instant means of identifying who is an “insider” and who is not?

Figure 8: Representations of Oannes and the Apkallu in Mesopotamian art and sculpture where they are frequently depicted as composite fish-man or bird-man figures.

And what might have been the purpose of such a brotherhood?

Curiously enough, in both Mexico and Mesopotamia where myths and traditions have survived in connection with the imagery and symbolism, we are left in no doubt as to what the purpose was. Stated simply it was to teach, to guide and to spread the benefits of civilization.

This, after all, was the explicit function of Oannes and the Apkallu sages who taught the inhabitants of Mesopotamia “how to plant seeds and then to harvest their fruits and v

egetables”—agriculture in other words—and who also taught them architectural and engineering skills, notably the building of temples. If they needed to be taught these things then they must have had no knowledge of them before the arrival of the sages. They must, in other words, have been nomadic hunter-gatherers just as the inhabitants of southeastern Turkey were until the sudden and surprising entry onto the world stage of Göbekli Tepe.

The same, it transpires, was believed to be the case with the ancient inhabitants of Mexico before the arrival of Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent, who came to teach them the benefits of settled agriculture and the skills necessary to build temples. Although this deity is frequently depicted as a serpent, he is more often shown in human form—the serpent being his symbol and his alter ego—and is usually described as “a tall bearded white man”18 … “a mysterious person … a white man with a strong formation of body, broad forehead, large eyes and a flowing beard.”19 Indeed, as Sylvanus Griswold Morley, the doyen of Mayan studies, concluded, the attributes and life history of Quetzalcoatl:

are so human that it is not improbable that he may have been an actual historical character … the memory of whose benefactions lingered after his death, and whose personality was eventually deified.20

The same could very well be said of Oannes—and just like Oannes at the head of the Apkallu (likewise depicted as prominently bearded) it seems that Quetzalcoatl traveled with his own brotherhood of sages and magicians. We learn that they arrived in Mexico “from across the sea in a boat that moved by itself without paddles,”21 and that Quetzalcoatl was regarded as having been “the founder of cities, the framer of laws and the teacher of the calendar.”22 The sixteenth century Spanish chronicler, Bernardino de Sahagun, who was fluent in the language of the Aztecs and took great care to record their ancient traditions accurately, tells us further that:

Underworld: The Mysterious Origins of Civilization

Underworld: The Mysterious Origins of Civilization The Master Game: Unmasking the Secret Rulers of the World

The Master Game: Unmasking the Secret Rulers of the World America Before

America Before Entangled

Entangled War God: Nights of the Witch

War God: Nights of the Witch War God: Return of the Plumed Serpent

War God: Return of the Plumed Serpent The Message of the Sphinx AKA Keeper of Genesis

The Message of the Sphinx AKA Keeper of Genesis Fingerprints of the Gods

Fingerprints of the Gods The Sign and the Seal

The Sign and the Seal The Mars Mystery: The Secret Connection Between Earth and the Red Planet

The Mars Mystery: The Secret Connection Between Earth and the Red Planet Magicians of the Gods: The Forgotten Wisdom of Earth's Lost Civilization

Magicians of the Gods: The Forgotten Wisdom of Earth's Lost Civilization War God

War God Underworld

Underworld The Mars Mystery

The Mars Mystery Magicians of the Gods

Magicians of the Gods The Master Game

The Master Game