- Home

- Graham Hancock

Fingerprints of the Gods Page 21

Fingerprints of the Gods Read online

Page 21

Meanwhile, let us consider the Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead. Parts

of its contents are as old as the civilization of Egypt itself and it serves as

a sort of Baedeker for the transmigration of the soul. It instructs the

deceased on how to overcome the dangers of the afterlife, enables him to

assume the form of several mythical creatures, and equips him with the

passwords necessary for admission to the various stages, or levels, of the

underworld.12

Is it a coincidence that the peoples of Ancient Central America

preserved a parallel vision of the perils of the afterlife? There it was

6 The Mythology of Mexico and Central America, p. 148.

7 Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Ancient Quiche Maya, (English version by Delia

Goetz and Sylvanus G. Morley from the translation by Adrian Recinos), University of

Oklahoma Press, 1991, p. 163.

8 Ibid., 164.

9 Ibid., p. 181; The Mythology of Mexico and Central America, p. 147.

10 The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, (trans. R. O. Faulkner), Oxford University Press,

1969. Numerous Utterances refer directly to the stellar rebirth of the King, e.g. 248,

264, 265, 268, and 570 (‘I am a star which illumines the sky’), etc.

11 Ibid., Utt. 466, p. 155.

12 The Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, (trans. R. O. Faulkner), British Museum

Publications, 1989.

144

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

widely believed that the underworld consisted of nine strata through

which the deceased would journey for four years, overcoming obstacles

and dangers on the way.13 The strata had self-explanatory names like

‘place where the mountains crash together’, ‘place where the arrows are

fired’, ‘mountain of knives’, and so on. In both Ancient Central America

and Ancient Egypt, it was believed that the deceased’s voyage through

the underworld was made in a boat, accompanied by ‘paddler gods’ who

ferried him from stage to stage.14 The tomb of ‘Double Comb’, an eighthcentury ruler of the Mayan city of Tikal, was found to contain a

representation of this scene.15 Similar images appear throughout the

Valley of the Kings in Upper Egypt, notably in the tomb of Thutmosis III,

an Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh.16 Is it a coincidence that the passengers

in the barque of the dead pharaoh, and in the canoe in which Double

Comb makes his final journey, include (in both cases) a dog or dogheaded deity, a bird or bird-headed deity, and an ape or ape-headed

deity?17

The seventh stratum of the Ancient Mexican underworld was called

Teocoyolcualloya: ‘place where beasts devour hearts’.18

Is it a coincidence that one of the stages of the Ancient Egyptian

underworld, ‘the Hall of Judgement’, involved an almost identical series

of symbols? At this crucial juncture the deceased’s heart was weighed

against a feather. If the heart was heavy with sin it would tip the balance.

The god Thoth would note the judgement on his palette and the heart

would immediately be devoured by a fearsome beast, part crocodile, part

hippopotamus, part lion, that was called ‘the Eater of the Dead’.19

Finally, let us turn again to Egypt of the Pyramid Age and the privileged

status of the pharaoh, which enabled him to circumvent the trials of the

underworld and to be reborn as a star. Ritual incantations were part of

the process. Equally important was a mysterious ceremony known as ‘the

opening of the mouth’, always conducted after the death of the pharaoh

13 Pre-Hispanic Gods of Mexico, p. 37.

14 The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya, pp. 128-9.

15 Reproduced in National Geographic Magazine, volume 176, Number 4, Washington

DC, October 1989, p. 468: ‘Double Comb is being taken to the underworld in a canoe

guided by the “paddler twins”, gods who appear prominently in Maya mythology. Other

figures—an iguana, a monkey, a parrot, and a dog—accompany the dead ruler.’ We learn

more of the mythological significance of dogs in Part V of this book.

16 Details are reproduced in John Romer, Valley of the Kings, Michael O’Mara Books

Limited, London, 1988, p. 167, and in J. A. West, The Traveller’s Key to Ancient Egypt,

Harrap Columbus, London, 1989, pp. 282-97.

17 In the case of Ancient Egypt the dog represents Upuaut, ‘the Opener of the Ways’, the

bird (a hawk) represents Horus, and the ape, Thoth. See The Traveller’s Key To Ancient

Egypt, p. 284, and The Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, pp. 116-30. For Ancient

Central America see note 15.

18 Pre-Hispanic Gods of Mexico, p. 40.

19 The Egyptian Book of the Dead (trans. E. A. Wallis Budge), Arkana, London and New

York, 1986, p. 21.

145

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

and believed by archaeologists to date back to pre-dynastic times.20 The

high priest and four assistants participated, wielding the peshenkhef, a

ceremonial cutting instrument. This was used ‘to open the mouth’ of the

deceased God-King, an action thought necessary to ensure his

resurrection in the heavens. Surviving reliefs and vignettes showing this

ceremony leave no doubt that the mummified corpse was struck a hard

physical blow with the peshenkhef.21 In addition, evidence has recently

emerged which indicates that one of the chambers within the Great

Pyramid at Giza may have served as the location for the ceremony.22

All this finds a strange, distorted twin in Mexico. We have seen the

prevalence of human sacrifice there in pre-conquest times. Is it

coincidental that the sacrificial venue was a pyramid, that the ceremony

was conducted by a high priest and four assistants, that a cutting

instrument, the sacrificial knife, was used to strike a hard physical blow

to the body of the victim, and that the victim’s soul was believed to

ascend directly to the heavens, sidestepping the perils of the

underworld?23

As such ‘coincidences’ continue to multiply, it is reasonable to wonder

whether there may not be some underlying connection. This is certainly

the case when we learn that the general term for ‘sacrifice’ throughout

Ancient Central America was p’achi, meaning ‘to open the mouth’.24

Could it be, therefore, that what confronts us here, in widely separated

geographical areas, and at different periods of history, is not just a series

of startling coincidences but some faint and garbled common memory

originating in the most distant antiquity? It doesn’t seem that the

Egyptian ceremony of the opening of the mouth influenced directly the

Mexican ceremony of the same name (or vice versa, for that matter). The

fundamental differences between the two cases rule that out. What does

seem possible, however, is that their similarities may be the remnants of

a shared legacy received from a common ancestor. The peoples of

Central America did one thing with that legacy and the Egyptians another,

but some common symbolism and nomenclature was retained by both.

This is not the place to expand on the sense of an ancient and elusive

connectedness that emerges from the Egyptian and Central American

evidence. Bef

ore moving on, however, it is worth noting that a similar

‘connectedness’ links the belief systems of pre-Colombian Mexico with

those of Sumer in Mesopotamia. Again the evidence is more suggestive of

an ancient common ancestor than of any direct influence.

20 See, for example, R. T. Rundle-Clark, Myth and Symbol in Ancient Egypt, Thames &

Hudson, London, 1991, p. 29.

21 Henri Frankfort, Kingship and the Gods, University of Chicago Press, 1978, p. 134. The

Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, e. g. Utts. 20, 21.

22 Robert Bauval and Adrian Gilbert, The Orion Mystery, Wm. Heinemann, London, 1994,

pp. 208-10, 270.

23 The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya, pp. 40, 177.

24 Maya History and Religion, p. 175.

146

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

Take the case of Oannes, for example.

‘Oannes’ is the Greek rendering of the Sumerian Uan, the name of the

amphibious being, described in Part II, believed to have brought the arts

and skills of civilization to Mesopotamia.25 Legends dating back at least

5000 years relate that Uan lived under the sea, emerging from the waters

of the Persian Gulf every morning to civilize and tutor mankind.26 Is it a

coincidence that uaana, in the Mayan language, means ‘he who has his

residence in water’?27

Let us also consider Tiamat, the Sumerian goddess of the oceans and of

the forces of primitive chaos, always shown as a ravening monster. In

Mesopotamian tradition, Tiamat turned against the other deities and

unleashed a holocaust of destruction before she was eventually destroyed

by the celestial hero Marduk:

She opened her mouth, Tiamat, to swallow him.

He drove in the evil wind so that she could not close her lips.

The terrible winds filled her belly. Her heart was seized,

She held her mouth wide open,

He let fly an arrow, it pierced her belly,

Her inner parts he clove, he split her heart,

He rendered her powerless and destroyed her life,

He felled her body and stood upright on it.28

How do you follow an act like that?

Marduk could. Contemplating his adversary’s monstrous corpse, ‘he

conceived works of art’,29 and a great plan of world creation began to

take shape in his mind. His first move was to split Tiamat’s skull and cut

her arteries. Then he broke her into two parts ‘like a dried fish’, using

one half to roof the heavens and the other to surface the earth. From her

breasts he made mountains, from her spittle, clouds, and he directed the

rivers Tigris and Euphrates to flow from her eyes.30

A strange and violent legend, and a very old one.

The ancient civilizations of Central America had their own version of

this story. Here Quetzalcoatl, in his incarnation as the creator deity, took

the role of Marduk while the part of Tiamat was played by Cipactli, the

‘Great Earth Monster’. Quetzalcoatl seized Cipactli’s limbs ‘as she swam

in the primeval waters and wrenched her body in half, one part forming

the sky and the other the earth’. From her hair and skin he created grass,

flowers and herbs; ‘from her eyes, wells and springs; from her shoulders,

25 Stephanie Dalley, Myths from Mesopotamia, Oxford University Press, 1990, p. 326;

Jeremy Black and Anthony Green, Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia,

British Museum Press, 1992, pp. 163-4.

26 Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia, p. 41.

27 Mysteries of the Mexican Pyramids, p. 169; The God-Kings and the Titans, p. 234.

28 New Larousse Encyclopaedia of Mythology, pp. 53-4.

29 Ibid., p. 54.

30 Ibid. See also Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia, p. 177.

147

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

mountains’.31

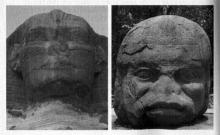

Are the peculiar parallels between the Sumerian and Mexican myths

pure coincidence or could both have been marked by the cultural

fingerprints of a lost civilization? If so, the faces of the heroes of that

ancestral culture may indeed have been carved in stone and passed down

as heirlooms through thousands of years, sometimes in full view,

sometimes buried, until they were dug up for the last time by

archaeologists in our era and given labels like ‘Olmec Head’ and ‘Uncle

Sam’.

The faces of those heroes also appear at Monte Alban, where they seem

to tell a sad story.

Monte Alban.

Monte Alban: the downfall of masterful men

A site thought to be about 3000 years old,32 Monte Alban stands on a vast

artificially flattened hilltop overlooking Oaxaca. It consists of a huge

rectangular area, the Grand Plaza, which is enclosed by groups of

pyramids and other buildings laid out in precise geometrical relationships

to one another. The overall feel of the place is one of harmony and

proportion emerging from a well-ordered and symmetrical plan.

Following the advice of CICOM, whom I had spoken to before leaving

Villahermosa, I made my way first to the extreme south-west corner of

the Monte Alban site. There, stacked loosely against the side of a low

31 Pre-Hispanic Gods of Mexico, p. 59; Inga Glendinnen, Aztecs, Cambridge University

Press, 1991, p. 177. See also The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya, p.

144.

32 Mexico, p. 669.

148

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

pyramid, were the objects I had come all this way to see: several dozen

engraved stelae depicting negroes and Caucasians ... equal in life ...

equal in death.

If a great civilization had indeed been lost to history, and if these

sculptures told part of its story, the message conveyed was one of racial

equality. No one who has seen the pride, or felt the charisma, of the great

negro heads from La Venta could seriously imagine that the original

subjects of these magisterial sculptures could have been slaves. Neither

did the lean-faced, bearded men look as if they would have bent their

knees to anyone. They, too, had an aristocratic demeanour.

At Monte Alban, however, there seemed to be carved in stone a record

of the downfall of these masterful men. It did not look as if this could

have been the work of the same people who made the La Venta

sculptures. The standard of craftsmanship was far too low for that. But

what was certain—whoever they were, and however inferior their work—

was that these artists had attempted to portray the same negroid

subjects and the same goatee-bearded Caucasians as I had seen at La

Venta. There the sculptures had reflected strength, power and vitality.

Here at Monte Alban the remarkable strangers were corpses. All were

naked, most were castrated, some were curled up in foetal positions as

though to avoid showers of blows, others lay sprawled slackly.

Archaeologists said the sculptures showed ‘the corpses of prisoners

captured in battle’.33

What prisoners? From where?

The location, after all, was Central America, the New World, thousands

of years before Columbus, so wasn’t it odd that these images of

battlefie

ld casualties showed not a single native American but only and

exclusively Old World racial types?

For some reason, orthodox academics did not find this puzzling, even

though, by their reckoning, the carvings were extremely old (dating to

somewhere between 1000 and 600 BC34). As at other sites, this time-frame

had been derived from tests on associated organic matter, not on the

carvings themselves, which were incised on granite stele and therefore

hard to date objectively.

Legacy

An as yet undeciphered but fully elaborated hieroglyphic script had been

found at Monte Alban,35 much of it carved on to the same stele as the

crude Caucasian and negro figures. Experts accepted that it was ‘the

33 The Cities of Ancient Mexico, p. 53.

34 The Ancient Kingdoms of Mexico, p. 53; Mexico, p. 671.

35 The Ancient Kingdoms of Mexico, pp. 53-4; The Cities of Ancient Mexico, p. 50.

149

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

earliest-known writing in Mexico’.36 It was also clear that the people who

had lived here had been accomplished builders and more than usually

preoccupied with astronomy. An observatory, consisting of a strange

arrowhead-shaped structure, lay at an angle of 45° to the main axis

(which was deliberately tilted several degrees from north-south).37

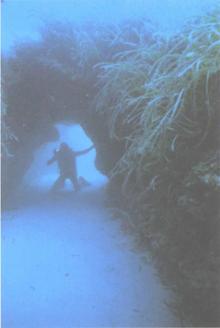

Crawling into this observatory, I found it to be a warren of tiny, narrow

tunnels and steep internal stairways, giving sightlines to different regions

of the sky.38

The people of Monte Alban, like the people of Tres Zapotes, left definite

evidence of their knowledge of mathematics, in the form of bar-and-dot

computations.39 They had also used the remarkable calendar,40 introduced

by the Olmecs and much associated with the later Maya,41 which predicted

the end of the world on 23 December AD 2012.

If the calendar, and the preoccupation with time, had been part of the

legacy of an ancient and forgotten civilization, the Maya must be ranked

as the most faithful and inspired inheritors of that legacy. ‘Time’ as the

archaeologist Eric Thompson put it in 1950, ‘was the supreme mystery of

Maya religion, a subject which pervaded Maya thought to an extent

without parallel in the history of mankind.’42

As I continued my journey through Central America I felt myself drawn

ever more deeply into the labyrinths of that strange and awesome riddle.

Underworld: The Mysterious Origins of Civilization

Underworld: The Mysterious Origins of Civilization The Master Game: Unmasking the Secret Rulers of the World

The Master Game: Unmasking the Secret Rulers of the World America Before

America Before Entangled

Entangled War God: Nights of the Witch

War God: Nights of the Witch War God: Return of the Plumed Serpent

War God: Return of the Plumed Serpent The Message of the Sphinx AKA Keeper of Genesis

The Message of the Sphinx AKA Keeper of Genesis Fingerprints of the Gods

Fingerprints of the Gods The Sign and the Seal

The Sign and the Seal The Mars Mystery: The Secret Connection Between Earth and the Red Planet

The Mars Mystery: The Secret Connection Between Earth and the Red Planet Magicians of the Gods: The Forgotten Wisdom of Earth's Lost Civilization

Magicians of the Gods: The Forgotten Wisdom of Earth's Lost Civilization War God

War God Underworld

Underworld The Mars Mystery

The Mars Mystery Magicians of the Gods

Magicians of the Gods The Master Game

The Master Game