- Home

- Graham Hancock

Fingerprints of the Gods Page 18

Fingerprints of the Gods Read online

Page 18

legendary Olmec homeland. The oil industry proliferates here now, where

rubber trees once flourished, transforming a tropical paradise into

something resembling the lowest circle of Dante’s Inferno. Since the oil

boom of 1973 the town of Coatzecoalcos, once easy-going but not very

prosperous, had mushroomed into a transport and refining centre with

air-conditioned hotels and a population of half a million. It lay close to

the black heart of an industrial wasteland in which virtually everything of

archaeological interest that had escaped the depredations of the Spanish

at the time of the conquest had been destroyed by the voracious

expansion of the oil business. It was therefore no longer possible, on the

basis of hard evidence, to confirm or deny the intriguing suggestion that

the legends seemed to make: that something of great importance must

once have occurred here.

1 The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya, p. 126.

2 Aztecs: Reign of Blood and Splendour, p. 50.

122

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

The Olmec sites of Tres Zapotes, San Lorenzo and La Venta along the

Gulf of Mexico, with other Central American archaeological sites.

I remembered that Coatzecoalcos meant ‘Serpent Sanctuary’. It was

here, in remote antiquity, that Quetzalcoatl and his companions were said

to have landed when they first reached Mexico, arriving from across the

sea in vessels ‘with sides that shone like the scales of serpents’ skins’.3

And it was from here too that Quetzalcoatl was believed to have sailed

(on his raft of serpents) when he left Central America. Serpent Sanctuary,

moreover, was beginning to look like the name for the Olmec homeland,

which had included not only Coatzecoalcos but several other sites in

areas less blighted by development.

First at Tres Zapotes, west of Coatzecoalcos, and then at San Lorenzo

and La Venta, south and east of it, numerous pieces of characteristically

Olmec sculpture had been unearthed. All were monoliths carved out of

basalt and similarly durable materials. Some took the form of gigantic

heads weighing up to thirty tons. Others were massive stelae engraved

with encounter scenes apparently involving two distinct races of mankind,

neither of them American-Indian.

Whoever had produced these outstanding works of art had obviously

belonged to a refined, well organized, prosperous and technologically

advanced civilization. The problem was that absolutely nothing remained,

except the works of art, from which anything could be deduced about the

character and origins of that civilization. All that seemed clear was that

‘the Olmecs’ (the archaeologists were happy to accept the Aztec

designation) had materialized in Central America around 1500 BC with

their sophisticated culture fully evolved.

3 Fair Gods and Stone Faces, pp. 139-40.

123

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

Santiago Tuxtla

We passed the night at the fishing port of Alvarado and continued our

journey east the next day. The road we were following wound in and out

of fertile hills and valleys, giving us occasional views of the Gulf of

Mexico before turning inland. We passed green meadows filled with flame

trees, and little villages nestled in grassy hollows. Here and there we saw

private gardens where hulking pigs grubbed amongst piles of domestic

refuse. Then we crested the brow of a hill and looked out across a giant

vista of fields and forests bound only by the morning haze and the faint

outlines of distant mountains.

Some miles farther on we dropped into a hollow; at its bottom lay the

old colonial town of Santiago Tuxtla. The place was a riot of colour:

garish shop-fronts, red-tile roofs, yellow straw hats, coconut palms,

banana trees, kids in bright clothes. Several of the shops and cafés were

playing music from loudspeakers. In the Zocalo, the main square, the air

was thick with humidity and the fluttering wings and songs of bright-eyed

tropical birds. A leafy little park occupied the centre of this square, and in

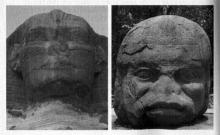

the centre of the park, like some magic talisman, stood an enormous grey

boulder, almost ten feet tall, carved in the shape of a helmeted African

head. Full-lipped and strong-nosed, its eyes serenely closed and its lower

jaw resting squarely on the ground, this head had a sombre and patient

gravity.

Here, then, was the first mystery of the Olmecs: a monumental piece of

sculpture, more than 2000 years old, which portrayed a subject with

unmistakable negroid features. There were, of course, no African blacks

in the New World 2000 years ago, nor did any arrive until the slave trade

began, well after the conquest. There is, however, firm

palaeoanthropological evidence that one of the many different migrations

into the Americas during the last Ice Age did consist of peoples of

negroid stock. This migration occurred around 15,000 BC.4

Known as the ‘Cobata’ head after the estate on which it was found, the

huge monolith in the Zocalo was the largest of sixteen similar Olmec

sculptures so far excavated in Mexico. It was thought to have been carved

not long before the time of Christ and weighed more than thirty tons.

Tres Zapotes

From Santiago Tuxtla we drove twenty-five kilometres south-west through

wild and lush countryside to Tres Zapotes, a substantial late Olmec centre

believed to have flourished between 500 BC and AD 100. Now reduced to a

series of mounds scattered across maize fields, the site had been

extensively excavated in 1939-40 by the American archaeologist Matthew

4 Ibid., p. 125.

124

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

Stirling.

Historical dogmatists of that period, I remembered, had held

tenaciously to the view that the civilization of the Mayas was the oldest in

Central America. One could be precise about this, they argued, because

the Mayan dot-and-bar calendrical system (which had recently been

decoded) made possible accurate dating of huge numbers of ceremonial

inscriptions. The earliest date ever found on a Mayan site corresponded

to AD 228 of the Christian calendar.5 It therefore came as quite a jolt to

the academic status quo when Stirling unearthed a stela at Tres Zapotes

which bore an earlier date. Written in the familiar bar-and-dot calendrical

code used by the Maya, it corresponded to 3 September 32 BC.6

What was shocking about this was that Tres Zapotes was not a Maya

site—not in any way at all. It was entirely, exclusively, unambiguously

Olmec. This suggested that the Olmecs, not the Maya, must have been

the inventors of the calendar, and that the Olmecs, not the Maya, ought

to be recognized as ‘the mother culture’ of Central America. Despite

determined opposition from gangs of furious Mayanists the truth which

Stirling’s spade had unearthed at Tres Zapotes gradually came out. The

Olmecs were much, much older than the Maya. They’d been a smart,

civilized, technologically advanced people and they did, indeed, appear to

have invented the bar-and-dot system of calendrical notation, with the

enigmatic starting date of 13 August 3114 BC, which predicted the end of

the world in AD 2012.

Lying close to the calendar stela at Tres Zapotes, Stirling also unearthed

a giant head. I sat in front of that head now. Dated to around 100 BC,7 it

was approximately six feet high, 18 feet in circumference and weighed

over 10 tons. Like its counterpart in Santiago Tuxtla, it was unmistakably

the head of an African man wearing a close-fitting helmet with long chinstraps. The lobes of the ears were pierced by plugs; the pronounced

negroid features were furrowed by deep frown lines on either side of the

nose, and the entire face was concentrated forwards above thick, downcurving lips. The eyes were open and watchful, almond-shaped and cold.

Beneath the curious helmet, the heavy brows appeared beetling and.

angry.

Stirling was amazed by this discovery and reported,

The head was a head only, carved from a single massive block of basalt, and it

rested on a prepared foundation of unworked slabs of stone ... Cleared of the

surrounding earth it presented an awe-inspiring spectacle. Despite its great size

the workmanship is delicate and sure, the proportions perfect. Unique in character

among aboriginal American sculptures, it is remarkable for its realistic treatment.

The features are bold and amazingly negroid in character ...8

5 Mexico, p. 637. See also The Ancient Kingdoms of Mexico, p. 24.

6 Ibid.

7 Mexico, p. 638.

8 Matthew W. Stirling, ‘Discovering the New World’s Oldest Dated Work of Man’, National

125

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

Soon afterwards the American archaeologist made a second unsettling

discovery at Tres Zapotes: children’s toys in the form of little wheeled

dogs.9 These cute artefacts conflicted head-on with prevailing

archaeological opinion, which held that the wheel had remained

undiscovered in Central America until the time of the conquest. The

‘dogmobiles’ proved, at the very least, that the principle of the wheel had

been known to the Olmecs, Central America’s earliest civilization. And if a

people as resourceful as the Olmecs had worked out the principle of the

wheel, it seemed highly unlikely that they would have used it just for

children’s toys.

Geographic Magazine, volume 76, August 1939, pp. 183-218 passim

9 Matthew W. Stirling, ‘Great Stone Faces of the Mexican Jungle’, National Geographic

Magazine, volume 78, September 1940, pp. 314, 310.

126

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

Chapter 17

The Olmec Enigma

After Tres Zapotes our next stop was San Lorenzo, an Olmec site lying

south-west of Coatzecoalcos in the heart of the ‘Serpent Sanctuary’ the

legends of Quetzalcoatl made reference to. It was at San Lorenzo that the

earliest carbon-dates for an Olmec site (around 1500 BC) had been

recorded by archaeologists.1 However, Olmec culture appeared to have

been fully evolved by that epoch and there was no evidence that the

evolution had taken place in the vicinity of San Lorenzo.2

In this there lay a mystery.

The Olmecs, after all, had built a significant civilization which had

carried out prodigious engineering works and had developed the capacity

to carve and manipulate vast blocks of stone (several of the huge

monolithic heads, weighing twenty tons or more, had been moved as far

as 60 miles overland after being quarried in the Tuxtla mountains).3 So

where, if not at ancient San Lorenzo, had their technological expertise

and sophisticated organization been experimented with, evolved and

refined?

Strangely, despite the best efforts of archaeologists, not a single,

solitary sign of anything that could be described as the ‘developmental

phase’ of Olmec society had been unearthed anywhere in Mexico (or, for

that matter, anywhere in the New World). These people, whose

characteristic form of artistic expression was the carving of huge negroid

heads, appeared to have come from nowhere.4

San Lorenzo

We reached San Lorenzo late in the afternoon. Here, at the dawn of

history in Central America, the Olmecs had heaped up an artificial mound

more than 100 feet high as part of an immense structure some 4000 feet

1 The Prehistory of the Americas, pp. 268-71. See also Jeremy A. Sabloff, The Cities of

Ancient Mexico: Reconstructing a Lost World, Thames and Hudson, London, 1990, p. 35.

Breaking the Maya Code, p. 61.

2 The Prehistory of the Americas, p. 268.

3 Aztecs: Reign of Blood and Splendour, p. 158.

4 ‘Olmec stone sculpture achieved a high, naturalistic plasticity, yet it has no surviving

prototypes, as if this powerful ability to represent both nature and abstract concepts

was a native invention of this early civilization.’ The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico

and the Maya, p. 15; The Ancient Kingdoms of Mexico, p. 55: ‘The proto-Olmec phase

remains an enigma ... it is not really known at what time, or in what place, Olmec culture

took on its very distinctive form.’

127

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

in length and 2000 feet in width. We climbed the dominant mound, now

heavily overgrown with thick tropical vegetation, and from the summit we

could see for miles across the surrounding countryside. A great many

lesser mounds were also visible and around about were several of the

deep trenches the archaeologist Michael Coe had dug when he had

excavated the site in 1966.

Coe’s team made a number of finds here, which included more than

twenty artificial reservoirs, linked by a highly sophisticated network of

basalt-lined troughs. Part of this system was built into a ridge; when it

was rediscovered water still gushed forth from it during heavy rains, as it

had done for more than 3000 years. The main line of the drainage ran

from east to west. Into it, linked by joints made to an advanced design,

three subsidiary lines were channelled.5 After surveying the site

thoroughly, the archaeologists admitted that they could not understand

the purpose of this elaborate system of sluices and water-works.6

Nor were they able to come up with an explanation for another enigma.

This was the deliberate burial, along specific alignments, of five of the

massive pieces of sculpture, showing negroid features, now widely

identified as ‘Olmec heads’. These peculiar and apparently ritualistic

graves also yielded more than sixty precious objects and artefacts,

including beautiful instruments made of jade and exquisitely carved

statuettes. Some of the statuettes had been systematically mutilated

before burial.

The way the San Lorenzo sculptures had been interred made it

extremely difficult to fix their true age, even though fragments of

charcoal were found in the same strata as some of the buried objects.

Unlike the sculptures, these charcoal pieces could be carbon-dated. They

were, and produced readings in the range of 1200 BC.7 This did not mean,

however, that the

sculptures had been carved in 1200 BC. They could

have been. But they could have originated in a period hundreds or even

thousands of years earlier than that. It was by no means impossible that

these great works of art, with their intrinsic beauty and an indefinable

numinous power, could have been preserved and venerated by many

different cultures before being buried at San Lorenzo. The charcoal

associated with them proved only that the sculptures were at least as old

as 1200 BC; it did not set any upper limit on their antiquity.

La Venta

We left San Lorenzo as the sun was going down, heading for the city of

Villahermosa, more than 150 kilometres to the east in the province of

5 The Ancient Kingdoms of Mexico, p. 36.

6 The Prehistory of the Americas, p. 268.

7 Ibid., pp. 267-8. The Ancient Kingdoms of Mexico, p. 55.

128

Graham Hancock – FINGERPRINTS OF THE GODS

Tabasco. To get there we rejoined the main road running from Acayucan

to Villahermosa and by-passed the port of Coatzecoalcos in a zone of oil

refineries, towering pylons and ultra-modern suspension bridges. The

change of pace between the sleepy rural backwater where San Lorenzo

was located and the pockmarked industrial landscape around

Coatzecoalcos was almost shocking. Moreover, the only reason that the

timeworn outlines of the Olmec site could still be seen at San Lorenzo

was that oil had not yet been found there.

It had, however, been found at La Venta—to the eternal loss of

archaeology ...

We were now passing La Venta.

Due north, off a slip-road from the freeway, this sodium-lit petroleum

city glowed in the dark like a vision of nuclear disaster. Since the 1940s it

had been extensively ‘developed’ by the oil industry: an airstrip now

bisected the site where a most unusual pyramid had once stood, and

flaring smokestacks darkened the sky which Olmec star-gazers must once

have searched for the rising of the planets. Lamentably, the bulldozers of

the developers had flattened virtually everything of interest before proper

excavations could be conducted, with the result that many of the ancient

structures had not been explored at all.8 We will never know what they

could have said about the people who built and used them.

Matthew Stirling, who excavated Tres Zapotes, carried out the bulk of

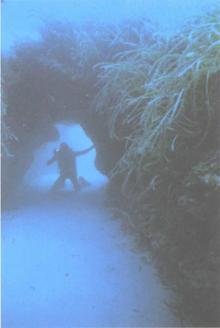

Underworld: The Mysterious Origins of Civilization

Underworld: The Mysterious Origins of Civilization The Master Game: Unmasking the Secret Rulers of the World

The Master Game: Unmasking the Secret Rulers of the World America Before

America Before Entangled

Entangled War God: Nights of the Witch

War God: Nights of the Witch War God: Return of the Plumed Serpent

War God: Return of the Plumed Serpent The Message of the Sphinx AKA Keeper of Genesis

The Message of the Sphinx AKA Keeper of Genesis Fingerprints of the Gods

Fingerprints of the Gods The Sign and the Seal

The Sign and the Seal The Mars Mystery: The Secret Connection Between Earth and the Red Planet

The Mars Mystery: The Secret Connection Between Earth and the Red Planet Magicians of the Gods: The Forgotten Wisdom of Earth's Lost Civilization

Magicians of the Gods: The Forgotten Wisdom of Earth's Lost Civilization War God

War God Underworld

Underworld The Mars Mystery

The Mars Mystery Magicians of the Gods

Magicians of the Gods The Master Game

The Master Game