- Home

- Graham Hancock

War God: Nights of the Witch Page 17

War God: Nights of the Witch Read online

Page 17

‘I’ll be happy to oblige,’ Cortés answered Ordaz. ‘He’ll be down on the main deck taking his dinner.’ He signalled to Sandoval. ‘Would you go and fetch him please? Ask for Luis Garrido. Any of the crew will know him.’

Sandoval was short with a broad, deep chest. His curly chestnut hair had receded almost to his crown, making him look peculiarly high-browed, but as though to compensate he had grown a curly chestnut beard, quite well maintained, that covered most of the lower half of his face. Although he presently owned no horse, lacked the means to purchase one and had enlisted as a private soldier, Cortés noted that his legs were as bandy as his own – the legs of a man who’d spent most of his life in the saddle.

When fat, perspiring, moustachioed Garrido entered the stateroom, he was in the midst of heaping complaints on Sandoval, wringing his hands and lamenting that he’d already told his story to Cortés and only wanted to finish eating his dinner and have a good night’s sleep.

Several of the captains had met Pedrarias, and others were familiar with the anchorage where he was supposedly mustering ships and men, but Garrido didn’t wilt under their close questioning, even naming and describing most of the vessels in his fleet. There was a danger of being caught out here – Garrido need only mention a single carrack or caravel that one of the captains knew for sure was not in Jamaica and his credibility would fall into doubt. Get two wrong and the whole exercise would become a fiasco. But so complete was the agent’s knowledge of shipping movements in the region, so accurate the details he reported and so fresh his recollections, that his imaginary fleet proved unsinkable.

Bravo, Cortés thought as Garrido left the stateroom to return to his dinner. A masterful performance. And, looking round the table, where an excited buzz of conversation immediately ensued, he could see that most of the captains were swaying his way – that escaping tonight on the ebb tide, to get a foothold in the New Lands and be the first to stake a claim there, was suddenly beginning to make sense to them.

In the end Escudero was the only Velazquista who still felt the matter should be reported to Velázquez. But he accepted the decision of the majority, and the authority of Cortés under clause twenty-three of the Instructions, to sail at once without informing the governor. ‘Under duress I accompany you,’ he said, ‘and under duress I stay silent. But what we are doing is not right. I fear we will all pay a price for it.’ He turned on Cortés. ‘You, sir,’ he said, ‘have no more conscience than a dog. You are greedy. You love worldly pomp. And you are addicted to women in excess …’

At this last remark, which seemed so irrelevant to the matter in hand, Alvarado burst out laughing. ‘Addicted to women in excess! What’s wrong with that, pray tell? If it’s a sin then I’d guess a few around this table are guilty of it! But what would you know or care of such things, Juan, when I’m told your own preferences run to little boys?’

Crash! Over went Escudero’s chair again and he was on his feet, lurching round the table towards Alvarado, his sword drawn, his knuckles white on its hilt. He didn’t get far before Puertocarrero, Escalante and Ordaz piled on top of him and disarmed him. Alvarado stayed where he was, one eyebrow sardonically raised.

‘Don Juan,’ Cortés said. ‘It seems you have forgotten.’

‘Forgotten what?’ Escudero was still struggling with his captors.

‘The agreement we all made an hour ago. Tonight we may trade insults with no man’s honour at stake. You have just insulted my conscience, for example, but do you see me at your throat with my sword?’

Escudero must have known he was trapped. ‘My apologies,’ he choked finally. ‘In my anger I forgot myself.’ He looked up at Alvarado: ‘But if you say such a thing tomorrow, I will kill you.’

‘Tomorrow is another day,’ said Cortés. He motioned to Sandoval. ‘Go and bring two of the men from the main deck, then take Don Juan below and lock him in the brig.’

‘The brig?’ Escudero spluttered. His face was suddenly purple. ‘You can’t do that to me!’

‘I think you’ll find I can,’ said Cortés. He unrolled the Instructions scroll, made a show of reading it. ‘Ah yes,’ he said, ‘here it is. Clause seventeen: “Captain-General may, on his sole discretion, restrain and if necessary incarcerate any member whose conduct becomes disruptive or threatens the success of the expedition …” To my mind, attacking Don Pedro with a sword in his own stateroom is disruptive and threatens our success.’

De León tried to intervene. ‘Please, Captain-General. Your point is made. Surely it’s not necessary to—’

‘It is,’ said Cortés, ‘absolutely necessary.’

Ordaz also seemed about to object but Cortés waved him down: ‘I’ll risk no distractions! Don Juan will be released in the morning. He can resume command of his ship then.’

Cortés had been expecting at least token opposition from the other captains, but Escudero was not well liked. Now that the decision had been made to embark immediately, it seemed no one wanted to speak up for him.

With an inner sigh of relief, Cortés realised his gamble had paid off. His authority over this unruly group had prevailed – at least for tonight.

‘Gentlemen,’ he said, ‘thank you for your support. I’m heartened by it. We’re embarking upon a great and beautiful enterprise, which will be famous in times to come. We’re going to seize vast and wealthy lands, peoples such as have never before been seen, and kingdoms greater than those of monarchs. Great deeds lie ahead of us; great dangers, too, but if you’ve got the stomach for it, and if you don’t abandon me, I shall make you in a very short time the richest of all men who have crossed the seas and of all the armies that have here made war.’

Everyone liked the idea of getting rich, so the speech went down well.

As the last of the captains hurried from the stateroom to make their ships ready to sail, Sandoval returned from locking up Escudero.

‘Ah,’ said Cortés. ‘Is the prisoner settled?’

‘Settled is not the word I’d use,’ said Sandoval. ‘He’s shouting and pounding on the walls of the brig.’

Cortés shrugged. ‘He can pound until dawn if he wants to; nobody’s going to take a blind bit of notice.’ He grinned: ‘Now listen, Sandoval, I’m glad you’re here. I’ve got soldier’s work for you to do tonight.’

Chapter Thirty

Santiago, Cuba, Thursday 18 February 1519

Gonzalo de Sandoval was from a respected hidalgo family, albeit one impoverished in recent years by a property dispute. He was born and bred a cavalier and university educated – natural officer material on every count. He was also from Medellín, Cortés’s home town in the north of Extremadura, and the Extremenos were famous for sticking together.

All these things, thought Bernal Díaz, made it easy to understand why Cortés had singled Sandoval out for responsibility yesterday, despite his obvious youth.

What made less sense – indeed, so much less sense he feared an elaborate practical joke – was that at the same ceremony, Cortés had also singled out Díaz himself, a man of poor family and almost no education, and elevated him from common soldado to alferez – ensign – the same rank he had bestowed on Sandoval.

Now, tonight, hard on the heels of his unexpected promotion, Díaz had been given his first command – not a very glamorous or prestigious command, to be sure, but one that was important and worthwhile.

Respectable work that made sense to him.

Cortés and Alvarado had entrusted him with the fabulous sum of three hundred gold pesos with which he was to purchase the entire contents of Santiago’s slaughterhouse – all the butchered meat and all the animals awaiting slaughter. In the unlikely event that three hundred pesos did not prove sufficient to buy everything, then Díaz was to commandeer whatever remained, carrying it away by force if necessary, but leaving a promissory note to cover payment.

‘Any problems with that?’ Cortés had asked.

‘I don’t want to get arrested, sir!’

‘Yo

u have my word that won’t happen. We are God’s soldiers, Díaz, doing God’s work and God’s work won’t wait …’

‘But if there’s trouble, sir?’

‘No need to call me “sir”. Don Hernando will do. Hernán when you get to know me better. I like to keep things informal if I can. As to trouble, there won’t be any – and if there is, I’ll protect you. You have my promise.’

It seemed Cortés was a man who made promises easily. But he was also the caudillo, captain-general of this great expedition to the New Lands, and Díaz’s best hope for finding wealth. So he’d shrugged and said, ‘That’s good enough for me … Don Hernando.’

He was having second thoughts now, though, as he stood in the middle of the slaughterhouse floor, his boots soiled with blood and straw, carcasses of pigs, cattle and sheep suspended from hooks all around him, night insects throwing themselves suicidally into the torches that lit up the whole room. In front of him, Fernando Alonso, the director of the slaughterhouse, was so angry that spit sprayed from his mouth and a vein in his right temple began to throb conspicuously. ‘No, I will not sell you any meat!’ he yelled. ‘Not for three hundred pesos or for three thousand pesos. I have a contract to feed the city.’

‘But with respect, sir,’ Díaz persisted, ‘we must have this meat. And all your livestock on the hoof as well.’

‘Livestock on the hoof! So you’ll have the whole of Santiago go hungry not only tomorrow but for the rest of the month! What kind of men are you?’

Díaz sought around for an answer and remembered what Cortés had told him. ‘We are soldiers of God,’ he said, ‘doing God’s work. Would you have us go hungry as we do it?’

‘I would have you honest,’ shouted Alonso, unleashing another geyser of spit. He had one of those personalities that made him seem physically bigger than he was, but in reality he was a small, bristling, bald man with rather long hairy arms, hefting a big cleaver in his right hand and wearing a bloody apron. Díaz had been surprised to find him already at work, slaughtering beasts and butchering them for Santiago’s breakfast; he had hoped at this time of night he could deal with some junior who wouldn’t know what he was doing.

Now, whether he liked it or not, he was into a full-fledged confrontation. Alonso put two fingers to his mouth, gave a piercing whistle, and five more men in bloody aprons made their way forward through the curtains of hanging carcasses.

Seeing they all carried cleavers and carving knives, Díaz glanced back over his shoulder to the door. He’d been given twenty men to move the meat and livestock. But he preferred persuasion to force so he’d left them outside and come in alone with the money.

Foolish hope!

‘La Serna,’ he yelled at the top of his voice, ‘Mibiercas! At the double, please!’

‘Look, for goodness’ sake please accept the money.’ Although it was Alonso and his five assistants who’d been trussed up, bruised and dishevelled on the floor, by Díaz’s soldiers, it was somehow Díaz who was pleading.

‘It’s not enough,’ said Alonso with conviction. ‘Even if this were a legal purchase, three hundred pesos is a joke. I’ll need at least fifteen hundred pesos to cover my costs and lost business.’

‘Then take the three hundred and I’ll write you a promissory note for the other twelve hundred. Don Hernando Cortés himself will cash it.’

‘Tonight?’

‘Yes. This very night. Come to the harbour within the hour and you’ll be paid.’

The men were released, quill, ink and paper were found, and Díaz wrote a note for one thousand two hundred pesos, payable by Cortés.

‘Come soon,’ Díaz told Alonso. ‘We’ll not wait for morning to sail.’

He left the slaughterhouse with his men, and began a forced march back to the harbour with two wagonloads of fresh and preserved meats and close to two hundred sheep, pigs and cattle on the hoof.

He didn’t know whether he’d done well or not and could only hope Cortés would be pleased.

Chapter Thirty-One

Santiago, Cuba, Thursday 18 February 1519

‘I must take you into my confidence,’ Cortés had told Gonzalo de Sandoval. ‘I trust I shall not regret doing so.’

The man’s charisma and charm were infectious and Sandoval was looking for adventure. ‘You’ll not regret it,’ he’d said.

The upshot was that he now knew much more about how things stood between Cortés and the governor than he wanted to, understood very clearly that what was happening tonight was indeed a coup against Velázquez, and had still allowed himself to be soft-talked by Cortés into participating.

Dear God! What was he thinking? He was taking the first step in what he’d always imagined would be an illustrious and honourable career, and he was quite likely to end up being hanged, drawn and quartered for it! For a moment Sandoval considered resigning his commission but immediately dismissed the idea from his mind. Whether or not he now regretted it, the fact was he’d given his word to Cortés, and a gentleman does not take his word back.

A scout had found the place, closer to the harbour than the city, where a squad of Velázquez’s palace guards lay in waiting. Cortés had not told Sandoval who they intended to ambush, only that there were twelve of them and that they were a threat to his plan – entrusted to Bernal Díaz – to supply the fleet with meat and live animals from the slaughterhouse. So much traffic on the road late at night was bound to arouse suspicion, and the guards couldn’t be permitted to disrupt the operation in any way, so Cortés had asked Sandoval to deal with them.

‘Deal with them, Don Hernando?’

‘We’re going to the New Lands to do God’s work,’ Cortés had said with a fierce light in his eyes, ‘so I want those guardsmen off the road fast and no longer threatening our meat supply – or our departure. Try to persuade them to join us. I’d prefer that. Bribe them – a few gold pesos can make all the difference. But if none of that works, then disarm them and tie them up – I’ll leave the details to you. They may put up a fight. Kill the lot of them if you have to. I won’t shed any tears.’

‘Will you be giving me men who’ll be prepared to kill fellow Spaniards … if we have to?’ Sandoval had asked, the question sticking in his gullet. He’d been through military academy in his youth, when his family still had money and position. He’d trained with the broadsword, the longsword and the cavalry sabre, he was judged a skilful horseman and had won top honours in the joust, but he’d never killed anyone before – let alone a Spaniard.

‘I’m giving you twenty-five of my best men,’ Cortés had replied. ‘They’ll kill anyone you tell them to kill.’

‘What if we’re caught? Taken prisoner? Arrested?’

‘Then I’ll protect you,’ said Cortés, looking him straight in the eye. ‘You have my promise.’

Wondering again what fatal enchantment had led him to agree to such a risky venture, Sandoval looked back at his twenty-five men. They marched silently, in good order, keeping a square of five ranks of five.

Their sergeant, the only one he’d talked to so far, was García Brabo, a lean grey-haired Extremeno with a hooked nose and a permanently sour expression, but the man you’d want beside you in a fight, Cortés had said. All the others looked like hardened killers too. Ferocious, stinking, hungry predators in filthy clothes, they wore strange combinations of scratched and battered plate and chain mail, and equally scratched and battered helmets, but were armed with Toledo broadswords and daggers of higher quality than their dress and general deportment would suggest. Many had shields – mostly bucklers, but also some of the larger, heart-shaped Moorish shields called adarga. Many carried additional weapons – halberds, lances, battle-axes, hatchets, war-hammers, maces, clubs. Five had crossbows and five were armed with arquebuses, the slow and cumbersome muskets that everyone was now raving about.

All in all, Sandoval thought, they were a formidable squad, his twenty-five, and he was stunned, amazed and perplexed not only that Cortés had given him command of them

in the first place, but also that they had so far obeyed him without question. The fact that he had no experience – unlike them – of killing men made him feel like a fraud. Worse still, he’d never even been in a skirmish before, let alone a proper battle against trained troops like the governor’s palace guard.

He prayed silently it would not come to that, but if it did he prayed he would not prove himself a coward.

Esteban, the wiry little scout, held up a warning hand, and Sandoval felt fear grip his belly like a fist. Reasons not to continue with this mad venture began to parade through his mind.

The plain truth was the moon was against them, two days away from full, shining brilliantly in a cloudless, tropical sky, flooding the winding road and the surrounding slopes with light. In an ideal world they would wait until after moonset to make the attack, but tonight that wasn’t an option. The guards had to be dealt with before the meat and livestock could be brought from the slaughterhouse and the fleet must sail at two o’clock in the morning. These were the facts, this was the emergency, and he was going to have to handle it frighteningly soon.

Loping along thirty paces ahead of the rest of the squad, Esteban reached a sharp bend where the road wound about a tall outcrop of rock. He stopped, crouched, peered round the corner and waved his hand urgently behind him, signalling to Sandoval to bring the men to a halt.

‘If I may suggest, sir,’ whispered García Brabo, his breath reeking of garlic, ‘you might think of going forward and striking up a conversation with the officer in charge of those guards. Likely he’ll be the same class of gentleman as yourself.’

‘A conversation …’

‘That’s right, sir. Bright young ensign newly out from Spain, making his way to Santiago, would naturally stop to pass the time of night. All very innocent and above board. Just keep him talking as long as you can. While you do that, me and half the men will have a go at climbing this lot.’ He pointed to the rocky outcrop rearing above them. ‘The scout says he knows a way over the top of it so we can get round behind them. I’ll leave Domingo’ – he gestured to another bearded ruffian – ‘in charge of the rest and we’ll come at them from both sides.’

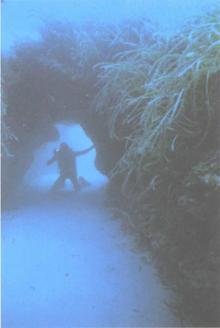

Underworld: The Mysterious Origins of Civilization

Underworld: The Mysterious Origins of Civilization The Master Game: Unmasking the Secret Rulers of the World

The Master Game: Unmasking the Secret Rulers of the World America Before

America Before Entangled

Entangled War God: Nights of the Witch

War God: Nights of the Witch War God: Return of the Plumed Serpent

War God: Return of the Plumed Serpent The Message of the Sphinx AKA Keeper of Genesis

The Message of the Sphinx AKA Keeper of Genesis Fingerprints of the Gods

Fingerprints of the Gods The Sign and the Seal

The Sign and the Seal The Mars Mystery: The Secret Connection Between Earth and the Red Planet

The Mars Mystery: The Secret Connection Between Earth and the Red Planet Magicians of the Gods: The Forgotten Wisdom of Earth's Lost Civilization

Magicians of the Gods: The Forgotten Wisdom of Earth's Lost Civilization War God

War God Underworld

Underworld The Mars Mystery

The Mars Mystery Magicians of the Gods

Magicians of the Gods The Master Game

The Master Game